Words of the year, BSL and Duolingo ditches Welsh

The latest language news + what to watch, read and listen to

Hi there, it’s Julia. I’m back with a new edition of Beyond Words, which from now on will be landing in your inbox sporadically, written by either me or Aisling. Thank you to all of you who have subscribed and keep reading our past newsletters. We wish you a great start to 2024 and stay tuned for more updates soon.

Let’s start with a recap of the words of the year. If 2023 had to be summed up with a single word, the Merriam-Webster dictionary says it would be “authentic”, as in “authentic cuisine” or “authentic voice” – the rise in the use of the word suggests we are all seeking authenticity everywhere. Meanwhile, the Oxford University Press went for “rizz”, a colloquial term defined as “style, charm, or attractiveness”, shortened form of the word “charisma”. The American YouTube and Twitch streamer Kai Cenat is widely credited with popularising the word in 2022, which then spread on TikTok.

Those are the words in English. For the words of the year in other languages, the Associated Press got its correspondents around the world to send in suggestions. The responses range from kuningi in South Africa, a Zulu term used to express frustration over several controversies happening at the same time, to Bharat, the ancient name for India, which sparked controversy when Prime Minister Narendra Modi used it in an official invite for the G20 summit. Every year in Japan, the top Buddist monk at the Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto writes the kanji character of the year on the temple balcony in what is a closely watched event. Yet this year’s word was remarkably unspiritual: the Japanese public summed up 2023 with the word zei (taxes), thanks to speculation about tax hikes to fund defence spending.

A recurring theme of this newsletter is how the language of Shakespeare continues to dominate the world. This opinion piece in the Guardian asks if it’s time to curb its power, and raises the question of fairness or “linguistic justice” (think of the amount of time and money Americans save in not having to learn English, compared to what Italians spend on learning it as a second language from a young age). However, many English monolinguals will tell you that they are the unlucky ones. Bilingualism or multilingualism have plenty of benefits after all, including improved memory.

But maybe the language we should all be learning is not spoken at all. The UK government recently announced that, starting in September 2025, secondary school students in England will be taught British Sign Language (BSL) in an attempt to advance inclusivity. BSL was officially recognised as a language in the UK last year, and the new course will be open to all pupils, who will learn around 1,000 signs. The program could have a positive impact on the quality of some basic services. A university in Bristol is training up future health workers in sign language after experts said it could help save lives. A primary school in Suffolk has even replaced French with sign language classes so that all of its pupils, some of whom have hearing loss, can communicate together.

For a prime example of how languages evolve, this piece chronicles how Africans are changing French through rap, literature, and stand-up comedy in countries like Ivory Coast. The Cité internationale de la langue française, a brand new institution dedicated to the French language, may have been inaugurated by Emmanuel Macron with great pomp last October, but more than 60 percent of French speakers now live on the African continent. Demographers predict that by 2060, that figure will have jumped to 85 percent.

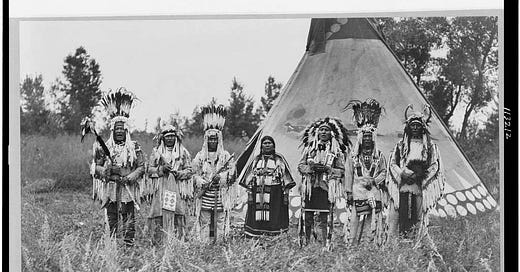

As the company that invented Mickey Mouse turns 100, this piece argues that Disney was great at creating folklore, “a set of reference points instantly recogniseable to almost everyone” which eventually became a language in itself – but do we still speak it? Another historic moment in Hollywood took place recently at the Golden Globes when Lily Gladstone became the first Indigenous woman to win the award for best actress and opened her victory speech in the Blackfoot language. “Hello my friends/relatives. My name is Eagle Woman. I am Blackfoot. I love you all,” she said in what is a customary way of showing respect in the language, before switching back to English and thanking her mum “who, even though she’s not Blackfeet, worked tirelessly to get our language into our classroom”.

The Blackfoot language has experienced a significant decrease in speakers since the 1960s and is classified as “severely endangered” by the UNESCO. In 2016 there were less than 5,000 speakers. Could Killers of the Flower Moon spark interest in learning the language? Ideally, people would be able to take it up easily on something like Duolingo, but the app has recently moved away from endangered and minority languages. It caused some controversy recently when it decided to “pause” its Welsh course despite high demand, in favour of more “popular” languages, such as Spanish. This piece argues that if we are to keep languages alive, we need robust forms of language learning that are not driven by profit.

What I’ve been up to:

Reading: Like many people, one of my recurring New Year’s resolutions is to read more and I recently downloaded Goodreads to keep proper track of what I’ve enjoyed. I just finished Sagittarius by Natalia Ginzburg, which I loved. It’s a story about two middle-aged Italian women with big dreams of opening an art gallery in Turin.

Writing: In November I went to Marbella to write about the city and its changing tourism industry for Monocle magazine. You can read it online here (paywall) or pick up a copy of Monocle’s annual The Escapist magazine, on newsstands now.

Watching: It’s awards season and I’m hoping that Anatomy of a Fall will keep winning prizes. I can’t decide if I liked Saltburn, Emerald Fennell’s latest film. I mostly didn’t but the film is still worth watching for the cast’s performances and the cinematography, which is inspired by vampire movies and Caravaggio paintings.

Listening: To this incredible episode of the Longform podcast with journalist Mona Chalabi (from November), who won a Pulitzer prize for this story on Jeff Bezos’s wealth for the New York Times Magazine. If you’re not one of her 494K followers on Instagram you’re missing out.

If you enjoyed reading this newsletter, please consider supporting us here.

Was this email forwarded to you? Click the button below to subscribe.

Julia Webster Ayuso is a Spanish-British freelance journalist based in Paris. Her writing has appeared in Time, The Guardian, The New York Times and Monocle. You can follow her on Instagram @jwebsterayuso

Aisling O’Leary is an Irish freelance journalist based in London. Her writing has appeared in Vogue, The Times, The Irish Independent and The Irish Times. You can follow her on Instagram @itspronouncedashling