The language of dating, familects and linguistic supersizing

We’re back! As we hope you have noticed, this newsletter has had to take a break while we sorted out our lives (and yes, caught up with friends over drinks). But we hope you’ll enjoy this issue, and as always please get in touch at beyondwordsnewsletter@gmail.com with your thoughts!

Hi, my name is Aisling and I’m a member of Seemingly-Single-Until-The-Day-I-Die.

Hi Aisling!

So, I’ve been “ghosted” (all communication cut without explanation), I’ve been “breadcrumbed” (flirtatious, but non-committal social signals were sent), then there was that person who “paperclipped” me for a while (AKA they dropped off the face of the planet after a few dates only to follow up months later – like that gormless Clippy on Microsoft Word just checking in if you need his help) and we can’t forget about Nathan “zombieing” week two of the pandemic (yep, he came back from the dead). Oh, of course I’ve also been “catfished”, can’t forget about that – he was a good five inches shorter than his profile said.

Readers, Roaring Twenties these are not. Dating language says a lot about the moment we’re living in and, well, we’re living in a moment that has birthed FODA, the Fear of Dating Again. According to the dating app Badoo, 78% of British people can’t remember how to date because of lockdown, and nearly half of millennials and Gen Z (49%) feel they have lost social skills.

But if we cast our eyes back to a century ago, they were the real romancing Roaring Twenties. It was an American columnist, George Abe, who coined the term “date” in 1896. Writing for the Chicago Record, Abe wrote about a clerk named Artie whose girlfriend was losing interest in him and beginning to see other men socially. When Artie confronted his fading love, he said: “I s’pose the other boy’s fillin’ all my dates?”

Post-war wealthy elites were going out, drinking, partying and “dating”. Cue new vocabulary for the activity that hadn’t really existed. Before that, you had courtship, a more strategised approach to pairing up. The idea of dating for funsies is a very modern phenomenon.

In the 1920s you might have gone to a “petting party” (the practice of amorously embracing, kissing, and caressing one's partner - just stopping short of sleeping together), endured a “blind date” (speaks for itself), or been a “two-timing tomcat” (absolute rascal). These are all words that cropped up in that hedonistic decade, in tandem with the wider acceptance of contraception (this was also the decade that saw the word “sexpert” come into play, as well as the phrase “to sleep around”).

The 1930s was the decade of “playing the field” and the 1940s was the era of “going steady”. There is speculation that the emphasis on early marriage (there were instructional films involved) during and after WWII was linked to the impulse to exclusively date one person. Some historians credit the shortage of male partners during the war; however, the end of the war did not end the practice, and “going steady” became even more pervasive after the war ended.

Nowadays, dating is heretofore to be known as “pandating” (dating during a pandemic), the Dutch can do some quarantinderen (using Tinder while quarantining) and apparently, the Japanese have been dabbling in doraibusurū o miai (drive-through matchmaking), in the empty car parks of wedding halls no less. - Aisling

Word of the month: Familect

Most of us have a secret language, a way of speaking with our loved ones that nobody else can understand (pet names, jokes, made-up words, an obscure reference to a film). It may feel weird or embarrassing, but it’s a very human bonding mechanism, and it has a name. The specific language used by a group of people among themselves is called a “familect”.

Lockdowns created the perfect breeding ground for familects, forcing us to spend much more time with the people we live with. But the whole point is they are private: they remain within the confines of the home. Perhaps the best example of a familect in pop culture can be found in the TV show Friends, which in last month’s much-awaited ‘Friends: The Reunion’ episode, its creator David Crane described as “that time in your life when your friends are your family”.

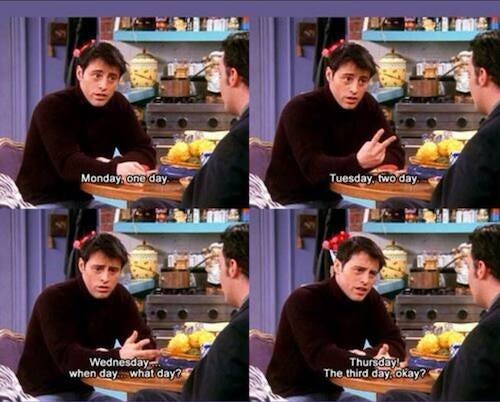

You may love it or hate it (and that reunion episode – let’s not even go there), but what makes Friends one of the most popular shows of all time was its ability to play with language to create memorable words and phrases. They were as simple as Ross repeatedly shouting “pivot!” at Chandler and Rachel carrying a sofa, Joey flirtatiously saying “how you doin’?”, or Ross insisting that “we were on a break!”.

The screenwriters also cleverly took existing words and gave them new meanings: “being someone’s lobster” meant being someone’s other half, “unagi” was a state of total awareness and “ichiban” became lipstick for men. Even nonsensical words like “transponster” and “phalange” stuck. Friends understood the power of the familect: it creates intimacy and a sense of belonging. You feel included, you’re part of the gang. - Julia

What we’re reading:

Don’t forget Africa, Google: The voice technology offered by Siri, Alexa and Google Assistant remains restricted to certain languages, accents and speech patterns, including Africa’s more than 1,000 languages. To remedy this, a crowdfunding project called Common Voice is gathering a database of African voices that developers can use to train their apps.

It’s French or bust: France struck down a bill last month that would allow schools to dedicate more hours to teaching in minority languages such as Basque, Breton and Catalan. The Constitutional Council described the bill, which aimed to boost regional languages, as “out of line with the constitution”, which stipulates that the language of the French Republic is French.

Going for gold: In an unexpected twist, it seems that Irish is looking likely to replace French as the second most popular language among A-level students in Northern Ireland, according to a report on language trends. For the past 20 years, Irish has slowly been catching up with French, which has seen a steep decline in popularity.

Supersize me: The English language loves extremes: we’re “shattered” after work, we’re “dying” to go on holiday. The relationship between the US and the UK was the “highest level of special” declared a certain former US president. According to psychologists, extroverts need more stimulation from language than introverts in order to feel any impact.

If you would like to support this newsletter, you can buy us a cup of coffee here. And if this email was forwarded to you, click the button below to subscribe.

About us:

Aisling O'Leary is an Irish journalist based in London, where she works at The Telegraph's travel desk. You can follow her on Twitter @JournoAsho

Julia Webster Ayuso is a Spanish-British freelance journalist based in Paris. Her writing has appeared in TIME, The Guardian and Monocle among others. You can follow her on Twitter @jwebsterayuso