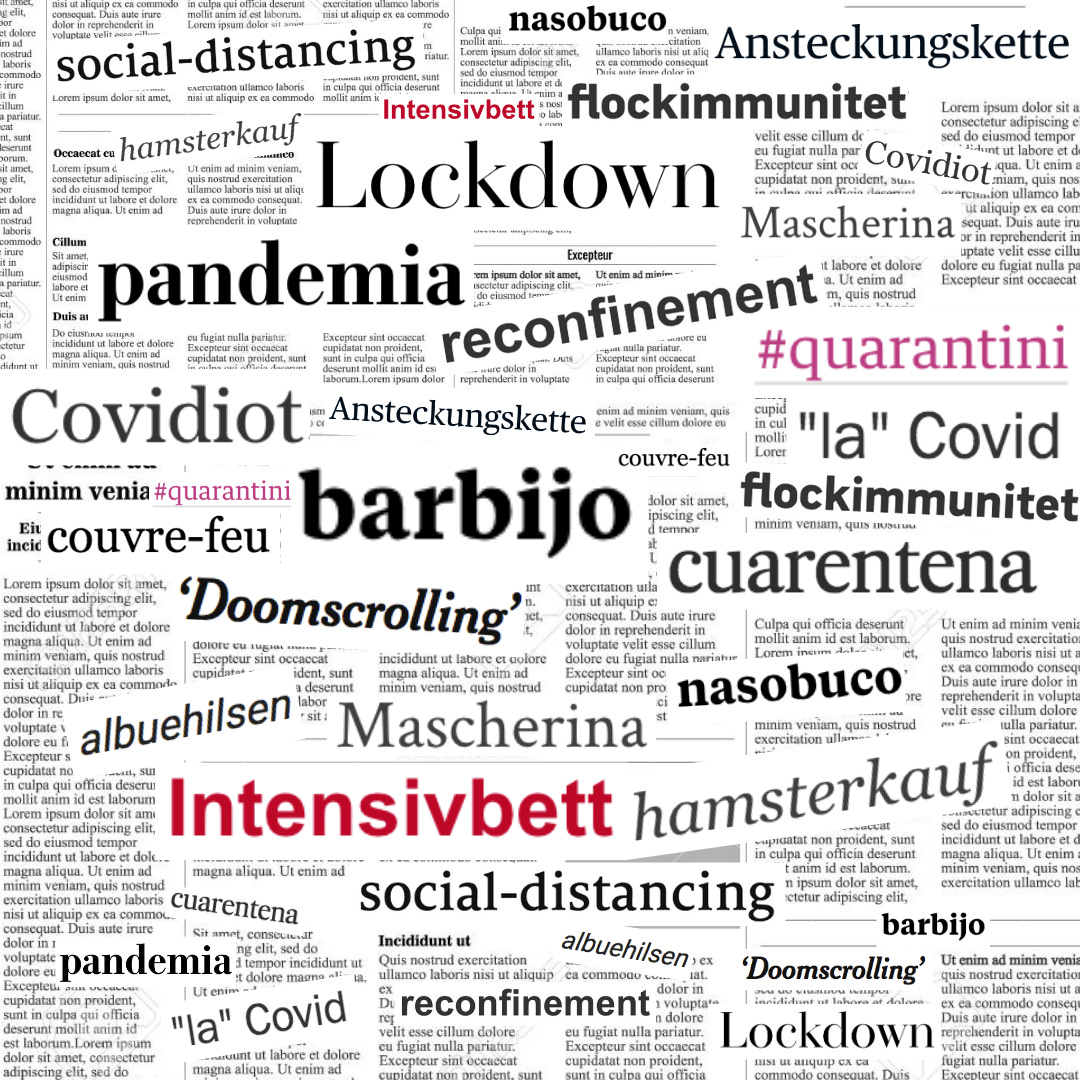

Never before has the world been so glad to see the year come to an end. But for linguists like us, there has been one small consolation during the pandemic (if you want to see the silver lining): 2020 was a great year for language.

Air bridges, locktails, support bubbles...Dictionaries all over the world scrambled to keep up to date with the amount of new terms that were quickly emerging to help us express these strange times. The Oxford English Dictionary even started releasing special updates, breaking with its usual schedule in a need to document the impact of Covid-19 on the English language. It’s hard to think back to just a year ago — the longed-for pre-Covid times — when “superspreader” and “quarantini” were yet to be invented.

This explosion in new words and phrases was a welcome break from the bad news. I loved finding out that the Germans, for example, came up with a brilliant word for panic buying: hamsterkauf, which refers to the way that hamsters store as much food as they can in their cheeks. In Spain, where I spent the first lockdown, we had words like zoompleaños (Zoom birthday) making life a bit less miserable, and the Dictionary of the Spanish language hurried to incorporate the several different words for mask, which vary depending on which country you’re in. Mascarilla is for Spain, but in Cuba they call it a nasobuco and in Argentina and Bolivia, you would be wearing a barbijo.

Meanwhile in France, where I’ve been living since June, there has been plenty of new vocab for me to learn (you can check out this list of phrases I put together for The Local France). But the main issue appeared to be a grammatical one. In a very French move, the Académie Française sparked a heated debate about the gender of the virus. Should you say “le covid” or “la covid”? According to the 400 year-old council for the French language, the correct form is “la covid” because it’s a maladie (illness), which is feminine. On the other hand you should say le coronavirus, because “virus” is masculine. Unfortunately, the verdict arrived a bit late, once the use of the masculine (the default) had already spread beyond control.

Adding new words to the dictionary is always exciting but you can’t beat a good classic, so a few old terms were brought back for reuse. “Community transmission” was first used in 1959, and “self-isolation” appeared in 1834, albeit for a different purpose: to describe countries that chose to detach themselves politically and economically from the rest of the world. “Curfew” brought with it memories of wartime and violence when it came back into use in October, as governments announced new restrictions. From the French couvre-feu (cover the fire), a curfew was common practice in the Middle Ages. A bell would ring at a certain hour indicating that all chimney fires should be put out before bed to prevent people from accidentally burning down entire villages. Over time it has come to signify a regulation requiring people to remain indoors between specified hours, but until recently many of us had never had to use it in a sentence — let alone experience its meaning in our daily lives.

This year has shown us how fast language can adapt in the face of social disruption, and that it can also be an important source of comfort and creativity. But it will still be years, if not decades, before we know which words will have a lasting effect, and which will remain a temporary tool for navigating a global crisis. Until then, as we continue to fight Covid, we’ll be keeping an eye out for any new coinages to lift our spirits. - Julia

What are your thoughts on the Kamala Harris Vogue cover controversy?

Word of the month: Pioneer

Clear the way! Make room! There’s a new pioneer in town and she’s on her way to Capitol Hill. That’s right, we’re talking about Kamala Harris, and not just because she’s a trailblazer, for “pioneer” is her secret service code name.

The Vice President-elect chose the name from a list that had been approved by the White House Communications Agency back in August when she had been confirmed as Joe Biden’s running mate. The name is a nod to the fact that she represents quite a few firsts for a major presidential party ticket: she’s the first black woman, the first Indian and Jamaican American, and will be the first ever female vice-president of the United States.

The use of code names was originally for security purposes and dates to a time when sensitive electronic communications were not routinely encrypted; today, the names simply serve for purposes of brevity, clarity, and tradition. Some other code names for you: Biden’s is Celtic (the proud Irish Catholic that he is), Obama’s is Renegade, and Trump’s is Mogul (go figure). Traditionally, all family members' code names start with the same letter (Melania’s is Muse and Michelle Obama’s is Renaissance).

Pioneer actually began as a military term. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) first dates it to 1517 when pioneers were originally foot soldiers who marched ahead of their regiment to dig trenches, clear roads and terrain, and otherwise prepare the way, with their picks and shovels, for the rest of the army. Harris is certainly doing just that: paving the way for women in politics and beyond. March on, comrades. See you next month. - Aisling

What we’re reading

Voice portraits. Would you have guessed that nearly 800 languages are spoken in New York City alone? Nope, not us either. This is what artist Ekene Ijeoma aims to show with his project A Counting: a collection of video and sound-based “voice portraits” of American cities. “I think it says a lot about the limits of representation,” Ijeoma told Fast Company about the number of languages spoken just in NYC. Anyone can get involved by counting from 1 to 100 in their native language on an automated phone call, or by helping transcribe other participant’s recordings.

Notes on woke. Love it or hate it, the term “woke” is one to stick around, as Kenya Hunt examines in The Guardian. Generally defined as “a perceived awareness of inequality and other forms of injustice that are normal in racial in nature”, its origins may be traced to Erykah Badu’s song “Master Teacher” from 2008 or further back to the cry of “Wake uuuuup!” in Spike Lee’s School Daze from 1988. But it’s just the last four years or so that we’ve been living in an era of woke-dom. Whether we’re talking about art, politics or climate change, you know yourself that we’re a tad more...awake.

Chair, parent, child, lawmaker. What do these words have in common, you ask? Well, dear reader, they are all gender neutral. This month, the US House of Representatives approved a proposal to “honour all gender identities” by changing to gender-inclusive pronouns and familial relationships. While it doesn’t ban the use of terms such as “he” or “she” in the House, it renames specific, official language found in the House rules.

Language learning boom. In the weeks after the WHO announced that Covid-19 had become a global pandemic, 30 million new learners started studying a language on Duolingo. That’s 67% more than the same period in 2019. And who are the eager beavers? That would be the British. The number of people in the UK learning a foreign language has risen twice as fast as the rest of the world in 2020. Despite leaving the EU, European languages top the list: French is a clear favourite, followed by Spanish, German and Italian.

“Smell it? That smell. A kind of smelly smell. A smelly smell that smells...smelly.” Don’t know what Mr. Krabs would make of the project to recreate old Europe but we’re all for it. There’s nothing quite like a certain scent — the language of the nose, if you will — to evoke a specific mood or recall a memory (the perfume Chanel “Chance” will always remind me of a trip to Venice). Named “Odeuropa”, the international research project will catalog and recreate different smells from past centuries, and may completely change the way we experience museums by adding a whole new sensory layer to them. Imagine taking a whiff of 19th century Paris while admiring a painting by Monet. Because that’s exactly how we would have spent the 1800s.

If you would like to support this newsletter, you can buy us a cup of coffee here. And if this email was forwarded to you, click the button below to subscribe.

About us:

Aisling O’Leary is an Irish journalist based in London, where she works at The Telegraph's travel desk. You can follow her on Twitter @JournoAsho

Julia Webster Ayuso is a Spanish-British freelance journalist based in Paris. Her writing has appeared in TIME, The Guardian and Monocle among others. You can follow her on Twitter @jwebsterayuso