Forensic linguistics, Spanish inclusivity and a ban on minority languages

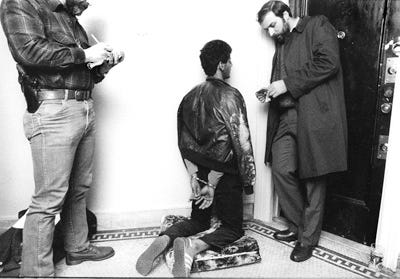

“Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law”. This is the most famous part of the “Miranda warning” given to suspects when they are arrested in the United States – a sentence we are all familiar with thanks to courtroom dramas. What you may not know is that it was named after Ernesto Miranda, a man who was arrested for the rape and murder of a woman in Phoenix in 1963. Though he confessed to the crime, it later turned out he had been coerced and intimidated by police, and the decision was overturned. Implemented in 1968, the “Miranda warning” given to suspects in custody reminds them of their right to counsel being present during police questioning. There is even a word for this: being “Mirandized”. It’s a reminder that language matters – and in legal settings your choice of words could have far-reaching consequences.

All of this is to say that I recently reported on the intersection of language and the law for The Dial magazine, which published an entire issue dedicated to language last month. In my piece “Can a Comma Solve a Crime?” I write about the world of forensic linguistics, in which people analyse linguistic evidence in criminal cases, often looking at the writing style of anonymous letters, for example, to find out who might be behind them. Forensic linguists argue that we each have a distinct way of speaking and writing – from the use of vocabulary to sentence structure, punctuation or even the use of emojis in text messages. We each have a “linguistic fingerprint”, if you will.

Should a country speak a single language? The New Yorker asks in a piece that delves into the challenges of studying and documenting India’s myriad tongues as the government pushes for more people to embrace Hindi. Meanwhile, the government of Slovakia is cracking down on minority languages with a new law prohibiting their use on public transport and places such as post offices, with fines of up to €15,000. In the Spanish-speaking world, language is evolving to be more inclusive, but not without some difficulty. While English has the existing words they/them to refer to non-binary people, romance languages have to be a bit more creative, given they are among the most gendered languages in the world. In Spanish, even saying “non-binary” requires specifying gender. That’s why “no binarie” has been given a new, neutral -e ending, instead of the gendered -a/-o.

Please don’t keep this newsletter to yourself. Share it with a friend! Or if you didn’t like it, with an enemy!

Academics have long wondered whether the language we speak influences – or even determines – the way we see the world. (The so-called Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, emerged in the early 20th century and has since been heavily contested.) A recent study says that bilingual people behave differently depending on the language they use – which may not come as a huge surprise. The study in question focuses on bilingual people who make a clear distinction between their “mother tongue” and their “second language”. The first is found to be more “emotionally rich”, while the second is less expressive but more practical.

However, this article in The Conversation argues that research into multilingualism should probably be taken with a pinch of salt. The problem is that much of it is not conducted in the world’s most multilingual societies, which means our understanding of it is probably skewed. Some of the most multilingual places in the world are in the “global south”: Africa, Latin America, much of Asia and Oceania. For example, Cameroon has over 250 languages alongside French and English, but studies of African multilingual contexts are “almost non-existent in high-impact scientific journals”.

What I’ve been up to:

Writing: “Can a Comma Solve a Crime?” in The Dial, plus a piece on the Catalan art of building human towers in Monocle’s December/January issue.

Reading: My friend Abi recently recommended Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These, which is the perfect Christmas read and can be devoured in an afternoon with a cup of tea.

Watching: I thought the adaptation of Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing was almost as good as the book itself – and that is saying something (pun intended). It has received some mixed reviews, however, and one of the subjects is suing Disney+ over it, so avoid googling if you don’t want spoilers!

Listening: To a (French) podcast called Shame on You, in which journalists Marine Pradel and Anne-Cécile Genre go over their reporting on the DSK affair in 2011, in which Nafissatou Diallo accused the director of the IMF and French presidential candidate of rape just a few years before #Metoo.